Your Guide to the Perfect Portfolio Review

Originally published as part of the #Tweetfolio column series of portfolio reviews at IFanboy.com and ComicsBeat.com.

Convention season’s started. Hundreds of aspiring comic book artists are putting the final touches to their portfolios, eager to meet editors and wow them with their work. If you are reading this there’s a very good chance you’re one of those. From my time doing portfolio reviews at Marvel (and before that at Harris Comics and since then as #Tweetfolio Reviews) I learned a lot about how to get the best out of a review.

A lot of artists treat these portfolio reviews like they are pass/fail. Worse, many artists treat them like being selected means they’ve won the lottery. This is not a competition. This is not a lottery. This is not the moment your life will change.

THIS IS A SNAPSHOT of where you are as an artist, at this time – Nothing more and nothing less. My most common advice at portfolio reviews involves telling an artist where I think they are in their development and how much further they need to go to catch the attentions of editors. I aim to be as practical as possible so the artists walk away with concrete points to address and concrete next steps to take. Timing is everything here and the best you can do, no matter how talented, is put yourself in position to take advantage when that perfect marriage of luck and opportunity arrives for you.

The unwelcome truth is 99 out of a 100 of you will likely walk away from the show not with a job, but with a new perspective. You will come to understand that comics is just like every other industry, with the same scarcity of jobs, the same demands of professionalism to acquire those jobs, and the same respect for seniority and qualifications and experience that you may lack. This isn’t a wall erected against you. It’s A CHALLENGE – and how you respond to that challenge will dictate the course of your future. Will you keep going in the face of these odds or do you believe in yourself enough to keep fighting?

The lay of the land at someplace like, say, Marvel is that they already employ well over a hundred artists on a regular basis, and there’s a few hundred more on their “bench” who could step in and take an open slot easily and immediately. To get a job at Marvel you will need to be better than someone they’re already working with. That could mean an editor will need to break a relationship with one artist to start one with you. Are you good enough to do that? No matter what you tell them about how fast and reliable you are, they KNOW that many of the ones they already work with are just as fast, just as reliable and much more well known and popular with their fanbase. This is what you are competing with, not just against talent but against history. Are you ready for that?

The best case scenario is there’s an opening that wasn’t there before. Perhaps artists are cycling off one series and onto another and the series they’re leaving behind needs a fill-in artist. Perhaps there’s a Point One issue or Villains Month type one-shot that needs a pinch hitter artist. Perhaps an event has a mini-series tie-in but no one available fits the artistic needs of that particular storyline. This is where calibrating your portfolio to the needs of a publisher will make or break you. Again: timing is everything, but can you take advantage of it?

If you’re not selected for a portfolio review don’t take it as a sign of failure. It’s just that you may not be what a publisher is looking for at this specific time. This is important: know thyself and know your publishers. Know that publishers’ editors by name and face and the artists they historically like to work with. Do not think your awesome art is the awesome art every publisher is looking for.

Craft a portfolio with work that speaks to their particular needs: Dynamite is launching James Bond comics and have revived the Gold Key characters with Solar and Turok. Dark Horse is reinvigorating their superhero line and launching Prometheus, Aliens and Predator comics. Valiant has imported former Marvel and DC talent of diverse styles and matched them with their diverse properties (from the grittier noir styling of Roberto de la Torre on Shadowman and the fun and organic lifework of Tom Fowler on Quantum and Woody). DC lately has brought in industry keystones like Dale Eaglesham, Paul Pelletier and Patrick Zircher. Marvel’s pushing newer talent like Dave Marquez, Valerio Schiti, Andre Lima Araujo, Gerado Sandoval, Kim Jacinto and Kris Anka and cover artists like Mike Del Mundo, Mukesh Singh and Alexander Lozano. And on and on. Ask yourself: Where can I find a home?

The last time I did portfolio reviews at New York Comic-Con I looked through 200 portfolios and selected just twenty for review. Of those twenty I thought only two ought to get Marvel work immediately and it turned out one had years back but fell off the radar and the other was always selected for portfolio reviews but the timing never worked out to find him an assignment. Can’t say it enough: timing is everything.

What set these particular two artists apart was they had crafted a unique and refined artistic voice — that fusion of storytelling skills, artistic style and an intangible spark. It would be difficult mistaking anyone else’s work for theirs. That’s special, that’s what allows you to literally stand out from the pile. Publishers aren’t looking for the next John Romita Jr, the next Jim Lee, the next Neal Adams. They are looking for the next YOU. Be honest with yourself: is your work too reverential to artists you grew up admiring? Is your work trying too hard to be something that it isn’t? Do you feel you are investing the full weight of your creativity in the layouts, the character design, the execution of the storytelling? If you are not honest with yourself on these points whoever reviews your portfolio will be.

Now for some final but important points:

*Don’t Poke the Bear:

I’ve been stopped running to the bathroom by aspiring artists and asked to look at portfolio. I am not kidding. I can understand the mentality: an artist is thinking this is the one chance they have to get a hold of an editor or talent scout, and running into one is a stroke of luck. Do not do this. You will smell of desperation. And though comic conventions are known to be full of all kinds of odors the smell of desperation is the smell that lingers most. This is why publishers have a set place, timeframe and procedure for these things so those on their staffs who want to review can do so when they want to and those who don’t won’t be harassed into doing something they don’t want to do. Do not force the choice on them by cornering them.

*Your Portfolio and Leave-Behind:

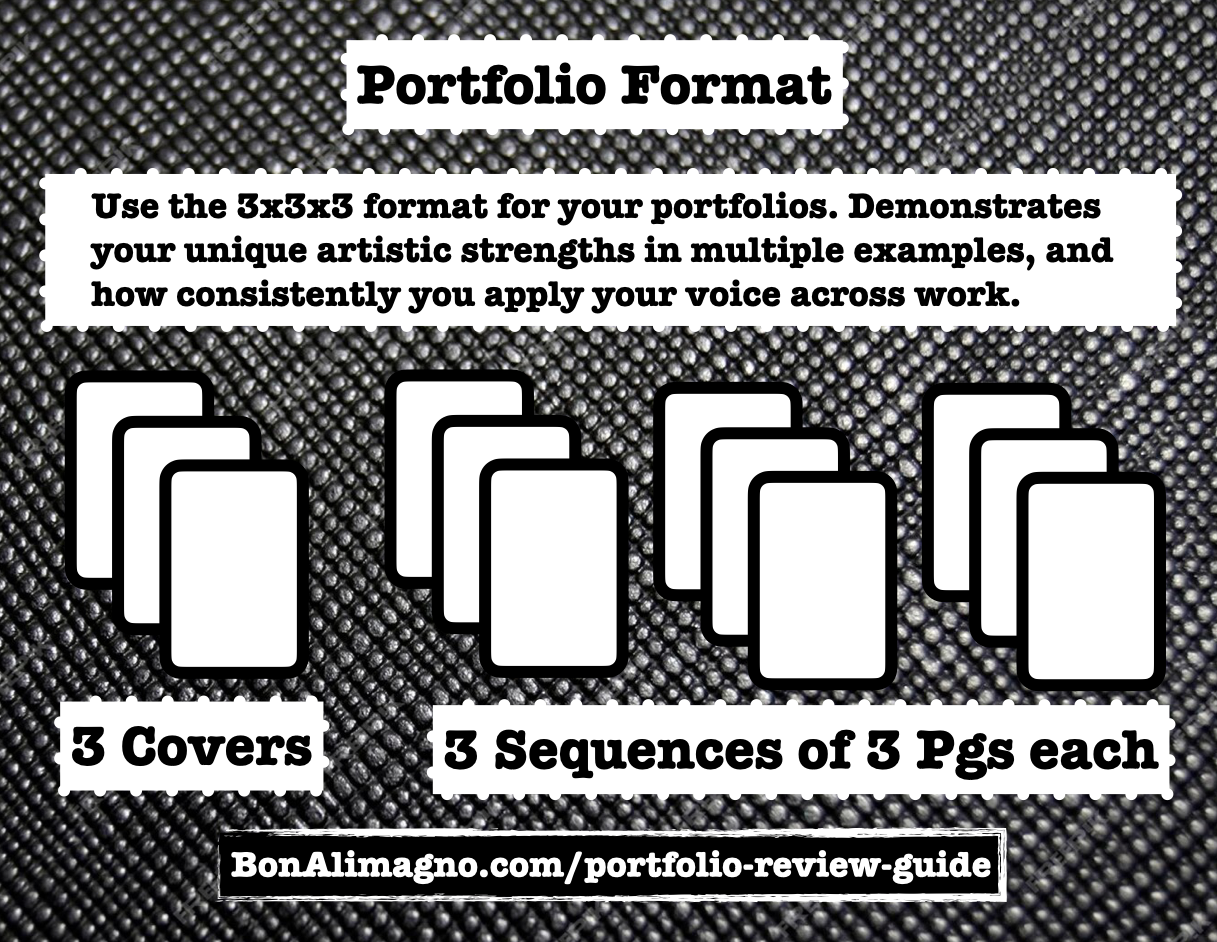

I have rarely seen a portfolio that matches this configuration but in my mind this is the bare minimum I’d need to give you a meaningful review.

-Three covers, each with a different character. This shows variety. Don’t just show the characters posed and clearly framed. Show them active, tell a story, and in the case of superhero characters show them strong, intimidating and powerful. It’s not enough that you drew a pretty picture. This is an ad for a comic book and it needs to be a highly effective one. Catch and arrest the readers’ attention. Sell some books.

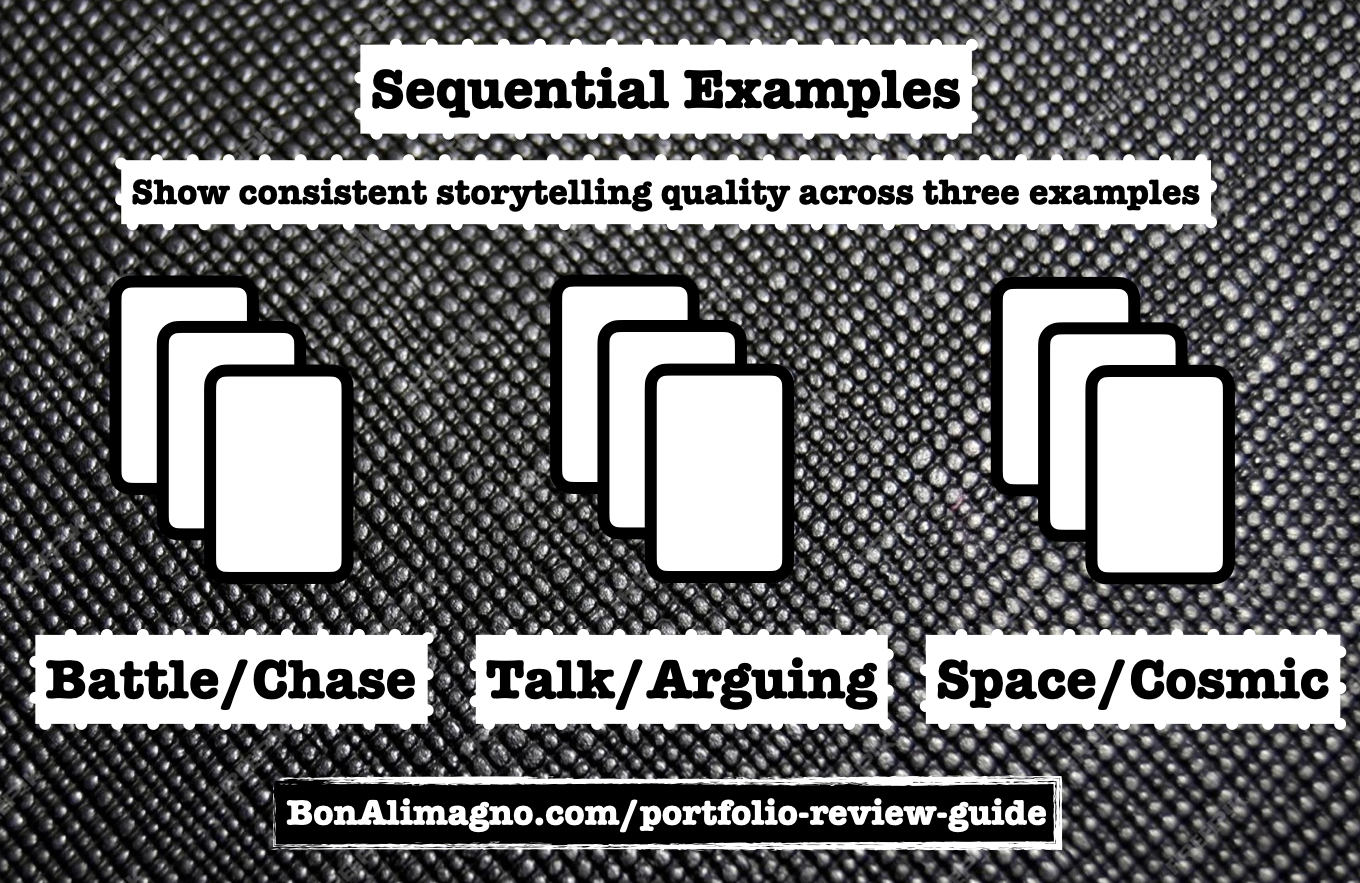

–Three sets of sequential samples, with three to five pages of consecutive storytelling.

I want to see this many to know you’re capable of not just diversity of subject matter, but consistency as well, especially when it comes to anatomy. I’ll question your choices to get at the root of your storytelling philosophy. Can I follow the story? Can my eye flow from one panel to another easily? Am I confused by what’s going on? Does your storytelling get me to go from one page to the next as if I’m carried along by a wave of excitement?

–Format:

Always include your full name and email address on every page.

Your leave-behind should be printed no larger than on 8.5” x 11” standard paper – no need for anything glossy or fancy. There’s no need to put them in a fancy binder either. The fancier the package the more I would think you’re trying to compensate for shortcomings in your work. I prefer paper stapled in one corner – that’s it. I don’t need to see a cover letter or resume. THE WORK WILL SPEAK FOR ITSELF.

I used to get asked all the time if I wanted to see samples printed on 11” x 17” and there’s no reason for that. If you think your pages need to be that large to see the full quality of your work, then you need to understand your work will not be printed at that size anyway. If I can’t fully appreciate your work at regular size then enlarging it won’t help things. You may think it’s too important to clearly show me detail, crosshatching and rendering, but I will always prioritize your storytelling. Storytelling is king.

If you have a leave-behind that is ashcan size I would prefer to take that home with me. This applies to anything you leave behind with any editor, agent or scout you meet: they’ll likely be going out right after the con for dinner and drinks with their fellow professionals. They don’t want to carry a lot with them. If you can leave behind something conveniently sized then it’ll be easier to carry and file away, and leave the impression that you care about not inconveniencing them. OR: leave a card with a link to your digital portfolio and some key art that allows editors to remember you.

Don’t drop originals in the drop box. That tells me you don’t know what you’re doing. You might as well take a $20 bill out of your wallet and submit that instead. Please don’t sadden me by doing that.

-Always Follow-Up

I used to always give my email to everyone I reviewed. Whether or not they reached out to me was their first test. Almost always only a few wrote back, even if I gave what I thought was a favorable review. Always follow-up. You can’t be in the right place at the right time without moving forward.

Good luck to everyone and have fun at your shows!

Addendum - July 2020

As part of Comics Experience's presence at C2E2 2020, I conducted portfolio reviews all three days of the convention at the Source Point Press booth.

I really want to focus on what I learned from the folks I was honored to review. These are more lessons I can generalize and apply to anyone submitting for a portfolio review, to any reviewer at any convention. This especially rings true for those submitting to a publisher, editor or talent scout who, as I did, may not have been super clear on what the expectations are. Speaking of which:

If you are unclear what the expectations and schedule are, do not hesitate to ask.

I'd released the sign-up and notification procedure via social media each morning, but that's not the best when everyone is already busy doing a thousand things the morning of a con. Folks should've waited till I emailed them directly to schedule a timeslot or let them know they were not selected. That may have been misunderstood or not communicated by the booth. A hand full of folks came up to the booth at the start of each session. I then had to ask them to wait because I'd already scheduled and confirmed sessions with other artists. This led to some awkward minutes where artists essentially stalked the booth waiting for me to be done with an artist for their turn. Lesson here: if you are confused, ask the talent scout or editor what’s expected of you, or lacking that ask the folks at the booth. At worst, this'll force folks like me to fix their procedures and arrange a new slot with you.

It should not be your responsibility as a talent to do the job of the talent scout. We scouts need to get our act together. We screw up just like anyone else. Hold us accountable.

Don't expect to be hired on the spot. Instead be prepared to answer level-setting questions to help you get hired.

Treat the review like a status update: are you where you want to be in your career? If not, what do you need to do to get there? Come away from the review with actionable steps.

I asked nearly every artist I reviewed in Chicago:

Which artist do you consider closest to your own style/which artists do you emulate?

I recommend having an answer to this regardless if anyone asks you. Bring that artist up in reviews yourself. It empowers reviewers to have a baseline of comparison when, frankly, they are struggling to find one which is often the case. Your style may be unlike anything we've seen before but if there's a baseline that YOU started from, that helps us figure out how you got from there to where you are now — and recommend next steps to get you where you really want to go. An artist may think they are on the right track when they are not, and it's up to the reviewer/scout (or me) to help set you straight. Years ago I asked this question of an artist and he pointed across the way and pointed to a booth. "Funny you ask that question: the artist I emulate the most is right there." And it was Howard Chaykin. I had to tell him his style didn't resemble Chaykin's at all, if anything he was drawing the opposite of Chaykin's style.

Two things could be happening here: 1) You may be emulating elements of an artist's style that are incompatible with your style. The result is a hybrid that is less than the sum of its constituent styles. Conversely 2) you're ready to be hired by any publisher, but your style is diluted version of the style you emulate -- time to turn it up to 11 and introduce unique touches only you can.

Speaking of the latter: develop a style that’s immediately identifiable. That’s the best way to elevate you above other similar artists. I’ve strongly suggested to a lot of artists to check out sports photography and imagine you’re trying to capture a shot that will win the front page of the Sports section. It’d need to be something that’s immediately arresting by itself and captures not just the most important moment but the most important millisecond of any particular set of actions. I also send around the photography of MMA photojournalist Esther Lin a lot. She’s my go to for capturing those moments — you can see the tension in the muscles, the flow and impact of the strikes, the gristle and blood flying off the combatants. Then the viewer fills in all the moments before and after themselves because you’ve gone to the effort of picking out the most exciting millisecond. I’ve found this is what attracts Marvel editors to artists the most and I’ve seen it evidenced over the years in folks like Oliver Coipel, Sara Pichelli, Stuart Immomen and now Russell Dauterman, Pepe Larraz and Valerio Schiti.

2) What are your short-term goals?

This is crucial so the scout/editor can first of all tell you if you're a fit for the publisher they are sitting at. (For example, Source Point Press does creator owned, but if you wanted to do a YA graphic novel a publisher that's been specializing in more adult fare may not be for you). This is also crucial if your intent is working at Marvel or Random House Graphix -- radically different answers and advice work backwards from whatever goals you have. "Being successful" or "Getting to the next level" may not be enough -- it's about understanding what your plan is and what from our experience can help you achieve that plan. You want to talk to editors and scouts who can have answers for you regardless of your goal -- these are folks who are more connected and in tune with the broader state of the industry than those who only know and care about what their publisher creates. If you are dead set on working with that publisher but being told you're not a fit, ask for specifics and then figure out for yourself if you're willing to bend your style and your goals to meet the publisher in the middle. But is there someone else you should be talking to, one who may have been waiting for just your style? Is there another online platform like Gumroad or Webtoon where you can easily find an audience instead of the direct market? A good scout will be able to give you these answers.

Finally:

I tell everyone at the start of a review that if what I advise doesn't resonate with you, feel free to completely ignore it.

Find an editor, talent scout who GETS YOU. Those are the folks who'll get you published and help you unlock your additional potential.

FAQ

I'd also like to see how to get that portfolio into their hands, besides conventions (conventions are not ideal for everyone, what other means do we have that are actually effective?)

I want to emphasize: no artist ever needed to go go a convention to get work. It can help but isn't necessary. I think every new colorist I broke into Marvel I did without ever meeting them in person, entirely over email, and with digital portfolios. Talent scouts like Rickey Purdin are completely fine with cold emails. I was, too. I'd never force anyone to get on a plane and fly to see me, that was nuts even before the pandemic.

If your goal is getting steady work, can you rely on email, website, and hustle?

The short answer is "No”. Social media for so many reasons is not reliable as a direct marketing channel. There's still too much of an ad industry infrastructure built up to make it seem like it is. But I expect in the years to come we'll see the data that demonstrates otherwise.

Go with your strongest, most direct to consumer marketing channel. That should be an email list/website, but if it's social media then stick with what's strongest and resonating with your clients. But everything I've been seeing points to email as the most effective channel.

Should one even mention unproveable stuff like, "I'm fast, professional, easy to work with" etc? Should you add in non-comic non cover/pin-up art like sketch cards, character designs, storyboards?

3x3x3 — three covers, and three consecutive sequential art pages from three different stories. I learn everything I need to know from these alone. Everything else is extra.

Nothing wrong with saying you’re on time, professional etc. Ideally you can give references of companies you’ve worked for, or other talent who can confirm. Ultimately it’s up to the editor if they want to take the risk, so provide evidence you are low risk.

What is your advice on how to find out what a specific editor is looking for, before you pitch?

Ask first. Really that's my advice for dealing with any editor at anytime. Otherwise you're just guessing.

Ping them on social media. Worse case they don't reply. The ones who are specifically looking may reply with exactly what they are looking for (as a broadcast for anyone else viewing their feeds). Email them if you you know them.

You could be more pro-active and predict upcoming needs, like do they need someone to fill-in for an event one-shot or something similar.

You could also ask, "what styles are you looking for?" and reconfigure your portfolio accordingly. There's a good chance the editor/talent scout doesn't know what they want yet, but will look at an artist's work and like it, but have nothing in the queue that fits that style. But the key also is demonstrating how flexible you can be -- like if they need a custom comic for the NBA, what can you do to demonstrate you’re a fit? If they need a custom comic for k-pop stars, what can you do to demonstrate that, that can sell in Korea? Maybe I'm going too far with these questions but it's all about probing for needs and then responding accordingly.

Detail what is a leave-behind and what goes in it? Is it just a selection from the portfolio?

Hopefully the leave behind is no more than the portfolio itself with a few extra pages This is also assuming the portfolio itself is short, no more than the 3x3x3. I've been ruthless over the years with recommending that leave behind's should be short and portable. Honestly, I'd love it if they were all no bigger than ashcan size. I still have leave behinds from 10-15 years ago that are no larger.

Usually when a talent scout/editor receives one, they are at a convention. Anyone accepting leave behinds probably already has a dozen (or in the case of a talent scout at Marvel/DC, dozens). They will then need to drop those off at their hotel or carry them to dinner. I, not rightfully so, would hold it against an artist that they gave me their landscape format hardcover which was breaking my back walking to the subway to dinner. (CB once scolded me for being mad about it. "It's a good book!")

It should also have your name, contact info, your website or online presence and a cover I can easily pick out of a stack of other leave behinds. If I had to choose between keeping a business card or keeping the leave behind, you want to make me want to keep the leave behind, so it'd have all the same info.

Is the portfolio itself still presented as originals?

Doesn't have to be. But if you're a penciler, I'd like to see just the original pencils. Doesn't need to be 11x17 -- I prefer 8.5 x11, and smaller comic book size really. I'm evaluating storytelling more than anything else and that should be reviewable at any size.

I should add: pencilers would sometimes present me with copies of fully inked pages. I'd ask to see the pencils and those would be literally tucked in the back or on their website and that's an extra layer of friction when they could've just shown the pencils first. Lots of pencilers also think they need to include fully inked, or fully inked and colored pages because that makes them look their best. It does. But problem is I don't want to see you at your best. I want to see you when it's just you and the page and nothing in between -- that's what my editors would be dealing with and I'm putting myself in their shoes as I review. I want to understand, what work an inker and a colorist would have to do to get you to your best self. That's more work for those folks as well as the editor. I want to see that you're a fully formed product from the jump and anything else would just be unlocking further potential to your work.

What are some questions you ask a lot other than which artist they want to emulate? What should I be prepared to tell you about pieces?

I'll often ask why they made certain storytelling choices if I didn't understand it, especially if what was happening wasn't clear to me or how we got there from the previous panel. Really I was trying to understand their thinking, and even if I didn't agree with their storytelling choice, if they were thoughtful about how they got there then I'd see that as a plus. The folks who would reply that they were just drawing what was in the script or couldn't give an answer threw up a red flag for me. Even if they drew like Travis Charest stylistically I knew they'd need too much hand holding by the editor to tell a story clearly.

I'd also ask why they might be switching styles from one set of samples to the other, if they showed different styles (like one set would have a grittier horror feel and another a smoother all-ages feel). Sometimes I'd see an artist employ a style that would work really well for an all-ages book but they used it for a horror sequence. My secret motivation behind asking is projecting if a style I liked could be used on another story where I think it would fit better. If the artist didn't understand why they made that choice then that was another red flag. That style likely would not be portable enough without a lot of hand holding by the editor.

Is there a type of sequential page that reviewers like to see?

For Marvel, I typically sent out one of three sample scripts: an Astonishing X-Men script with a very straight forward save the day sequence against Fin Fang Foom; an entire Thor issue with a selection of quiet and action packed scenes but all needing a grasp of Asgardian architecture and character design; and an Uncanny X-Force script with a few very complicated battle sequences. There were a few more scripts (like an Ultimates and a Spider-Man one) I cycled through but these were the three I sent out the most. All these were tests for different storytelling I was looking for:

Astonishing: Could you handle one character against one giant monster. I was really trying to assess the basics and see if you could resist temptation to go nuts with Fin Fang Foom -- the nuttier the design and the clearer the storytelling the better. But lots of folks when overboard and I could barely see any X-Men apart from the thousands of Fin Fang Foom scales.

Thor: stylistically could you handle an unearthly or cosmic sequence, really elevate it and bring yourself into it with your taste and design. There were some basic conversations and a few battles to choose from, but this was the stylistic showcase.

Uncanny X-Force: this was my master class -- if you could pass this test you could do well with anything. It's a very busy issue with a few very complex multi-character and multi-villain battles. I started sending out just one sequence in it instead of the entire issue to test whether an artist would go nuts with the splash page and make it unreadable. Rafael Albuquerque ultimately drew this issue so, yes, I kept comparing what I would get back to what Rafael would do. Honestly, many did well in comparison. If I'm remembering correctly, the samples Valerio Schiti and Pepe Larraz sent in of this sequence where the ones that got me obsessed with getting them work -- that didn't happen for both till much later but that’s a whole other story.

All this is to say, look at the sequentials you include to accomplish multiple things at once: what's your style, what are your storytelling chops, can you handle multiple characters and multiple environments. Definitely want to see variety. If you can only do one thing well, then you'll be a spot artist who gets fill-in issues every now and then. I'd be looking for someone who could eventually grow to take over the Avengers or X-Men or a franchise we haven't even launched yet. I can learn a lot by seeing Spider-Man and Mary Jane talk on a rooftop but learn a lot more from any of the above.

I would be interested in colorist specific "do's and don't's". I've seen a lot of different requests from mid-to-high level publishers, but would like to nail down a sweet spot.

I try to give "best practices" instead do's and don'ts. A scout for First Second would have very different criteria than one for Marvel. Boom may be looking for shorter YA targeted art styles while a DC scout may be looking how you look on any possible artist.

Daniel Ketchum, former Marvel editor and now with Wizards of the Coast, gave me this advice when I asked him what was he specifically looking for. And he was editing a lot of X-Men miniseries and X-Men legacy at the time so he needed a wide range and some specific things. I don't remember exactly what he told me so this is paraphrasing:

Outdoors on earth, natural light

Indoors, cave, darkness/low light source

Outer space, like fighting on the moon's surface or an orbiting station, so potentially oversaturated light sources

Demonstrate you can guide the eye across a page in any of these three or similar environments

What these drill down into is how do you handle:

Light sources

Competing light sources in dark environments

Reader focus from panel to panel in these environments

How cool or not cool, is fanart in a portfolio?

Short answer is “yes”, but the fan art then ought to be at a level that is immediately publishable as a cover. We want to know you’re a professional who can deliver complete, polished work. I am ruthless about recommending short, tight portfolios — three covers max, really. If fan art is taking one of those three slots there needs to be a very good reason and you’ll need to be able to explain it.

Let’s say you want to build a portfolio for writing, would 5-8 pages comic stories and a possible one shot be the way to go to showcase work?

That's tricky depending on a publisher's guidelines. Marvel (and typically all work for hire publishers) would not be able to read those for legal reasons. They may be accused of stealing the story. So they'd only ask for previously published work (fully drawn, etc).

If this means an anthology of creator-owned short stories, then sure. Make them varied and each have different artists to show your range. Give me bang for my buck — give me a complete emotional arc, as satisfying as a full issue or mini-series, with each 5-8 pgs of story. You want to demonstrate to an editor/talent scout you are a polished and complete package already and can scale to longer and longer stories immediately.

Best practices for follow up?

I'd ask how they want me to follow-up. Some might be real sticklers for what they want. I usually gave my email address. The first test would be, would they write me back at all? Few ever did -- maybe 1 in 5. Still baffles me.

Feel free to leave feedback and ask questions below or tweet me @karma_thief. #Tweetfolio banner by Jeremy Treece (@JeremyTreece).